Last week was the first Kepler Science Conference (or KeplerCon as I call it), at NASA Ames near Silicon Valley in Northern California. I attended with my grad student Tim Morton, and my new postdoc Phil Muirhead. Phil and I had back-to-back talks about our work on studying the least massive stars in the Kepler Field.

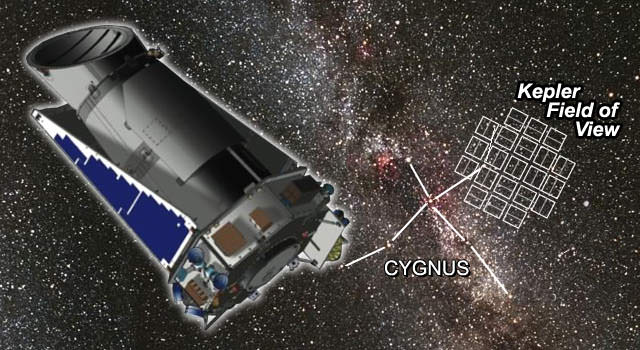

The Kepler Mission is a 1-meter space telescope that is staring at a 100 square-degree field of view. It measures the brightnesses of 160,000+ stars once every 30 minutes looking for the stars to periodically become dimmer, indicating the presence of an eclipsing (transiting) planet. Here's what a large signal looks like:

The Kepler Mission is exciting because it looks at so many stars and has such high precision. Here's a tiny signal from a tiny planet discovered by Kepler:

This is Kepler-22b, a 2.5 Earth-radius planet orbiting in its star's "habitable zone," which is the goldilocks region around the star where it is cool enough for liquid water. Pretty exciting!

Kepler is finding thousands of small planets like this, and each signal needs to be confirmed using telescopes on the ground. At the conference, Phil and I described our program to focus on the planet signals around very small stars known as red dwarfs, or M dwarfs.

Here's Phil's excellent talk:

Here's my talk right after Phil's:

And here are all of the talks from the conference:

Comments